NWA February 2021 Newsletter

Issue 21 - 02

President's Message

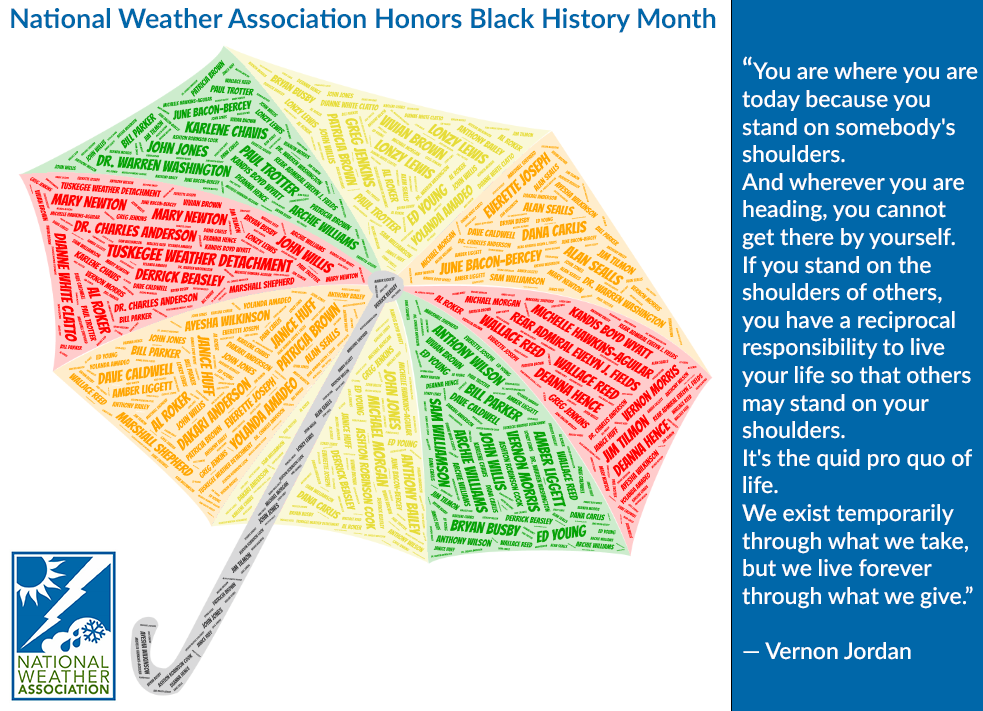

During its annual meeting last month, the American Meteorological Society announced it is renaming its award for broadcast meteorology after pioneering meteorologist June Bacon-Bercey. While other African-American women had presented weather forecasts on the air, she was the first female, African-American, degreed meteorologist to do so. Her story includes many other firsts, including being one of the first — if not the first — African-American woman to earn a degree in meteorology in 1954 and becoming the first African-American woman to earn the AMS’ Seal of Approval for TV Weathercasting in 1972. She worked in broadcasting, in the public sector, and as a collegiate instructor, winning numerous awards for merit along the way. She even won $64,000 on a game show, allowing her to endow a scholarship for students studying meteorology. Naming the broadcast award after her is a fitting tribute to someone with such an amazing and diverse career — Someone I admit I had not heard of before a couple of years ago. Someone else whose story I did not know until recently is Jim Tilmon. After graduating college and serving in the military, he went on to a decades-long career flying for American Airlines. He was only their third African-American pilot and was frequently mistaken for a skycap or flight attendant. Following that, he transitioned to a decades-long second career as a broadcaster in Chicago, first hosting a weekly program focusing on Black people and issues — the first such program, according to the station — then as an on-air forecaster, weather presenter, and aviation analyst beginning in the early 1970s. Tilmon passed away last month, and it was only then that I learned about him and his career. I like to consider myself reasonably well-plugged-in to our industry. I am active in the NWA and AMS. I am able to attend conferences. I read books, blog posts, and articles. I am on a weekly weather podcast. I even teach a broadcast meteorology course — a course that spends much of its first week exploring the people and historical forces that have shaped the broadcast weather industry. Yet I did not know of these two noteworthy, trailblazing people in our industry. And there are certainly others. This is one reason I am thankful for Black History Month and similar periods throughout the year. On one level, they are an opportunity to focus on people whom we really should be getting to know and stories that we should be telling all year long. And they help to address the natural blind spots that exist when we view our collective history through the lens of our experiences. The goal is to educate ourselves and broaden our perspective all year long so our understanding of the weather community’s story grows richer and ever more complete. To that end, the NWA is using this month to share not only stories of our past but also of our future. I am really excited that, as part of our celebration, we are highlighting recent winners of the NWA Foundation’s David Sankey scholarship. These talented people are writing not only their compelling stories but their own lines in our collective story as the NWA and the weather and climate enterprise. I believe you will enjoy getting to know them this month. Sources: https://physicstoday.scitation.org/do/10.1063/PT.6.6.20181023a/full/ https://www.encyclopedia.com/education/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/bacon-bercey-june-1932#E https://www.nbcchicago.com/news/local/jim-tilmon-longtime-nbc-5-forecaster-dies-at-86/2417684/ National Weather Association Honors Black History Month In honor of National Black History Month, the NWA Diversity Committee would like to invite you to celebrate, learn, and participate in events throughout this month to honor those African Americans who have been trailblazers in the field of meteorology; those who continue their contributions to the advancement of our field; and to the developing, ambitious, up and coming new generation of operational meteorologists.

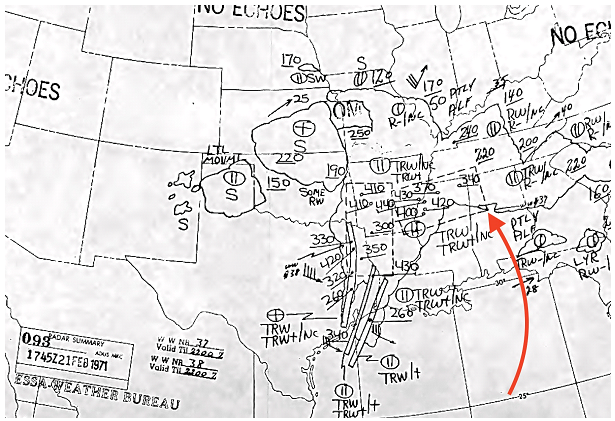

The umbrella consists of 35 highlighted names of notable African Americans in the meteorology field past and present. While it absolutely is not a complete list, it does contain many with “firsts” in the field. The colors chosen are representative of traditional African colors rich in symbolism and heritage. The shape of the umbrella was utilized not only for a weather theme to the graphic, but for a few other reasons. Umbrellas can be viewed as a sign of progress and protection; they also are a sign of privilege in thinking of U.S. Southern culture. On the flip side of privilege, the use of an umbrella has been seen as protection in protests. This occurred most recently in protests against police brutality in Seattle in 2020. This stood out significantly because Seattleites do not use umbrellas given their weather and climate. Typically, you can easily point out the transplants or tourists by their use of an umbrella when it is rainy. The umbrella is prominent in Creole culture in Second Line parade traditions celebrating life especially in the city of New Orleans. On this note, the design acknowledges the current state we are in with the continuing COVID pandemic and traditional gatherings being canceled such as Mardi Gras and Carnival. Submit Your Nominations for the 2021 Annual Awards More information on the NWA Annual Awards Program. The Carpenters’ Blizzard: 'Weather Technology ‘Now and Then’ The February 20-22, 1971, Carpenters Blizzard1 established records that still stand, including the State of Oklahoma’s single storm record (36 inches at Buffalo) and Wichita’s single storm record (12 inches). Wind gusts of 50 to 70 mph across the southern High Plains caused peak drifts of more than 25 feet. The drifts necessitated two weeks of desperate National Guard airlifts of hay to tens of thousands of cattle cut off from ranchers in Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas. In 2017, KOCO-TV in Oklahoma City called it “the most intense winter storm to ever hit the Sooner State.”

1971 Technology

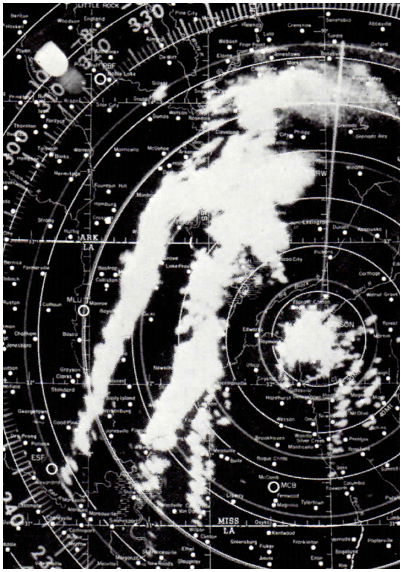

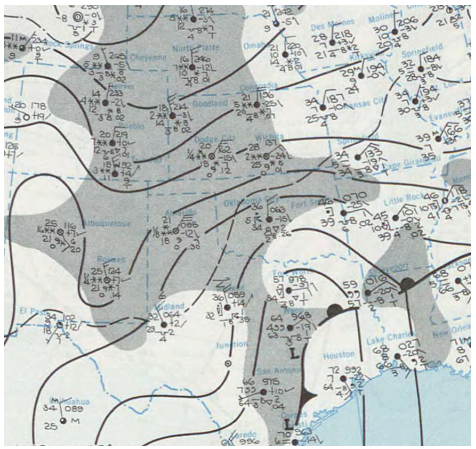

The available data was only marginally better at the Jackson, Mississippi, NWS office. Figure 2 depicts the black and white radar image at 4:20 p.m. when there were three tornadoes in progress (can you find their radar signatures?). The image in Figure 2 is an improvement over the radar displays in that era. It was created using a camera positioned above a plan-position indicator (PPI) radar scope with a hood that kept light out, allowing the camera shutter to be open for the entire 360-degree sweep. This produced a photograph of all the echoes on the screen. The meteorologist using this PPI had to deal with the storms fading on the display almost immediately after the radar “swept” them. For that reason, radars were operated in dark rooms, which made tracking spotter reports, typing warnings, and communicating information even more challenging. Doppler and dual-polarization (D-P) displays were not available. Figure 3. “Daily Weather Map,” 6 a.m. CST, February 21, 1971. I arrived in the map room around 11 a.m. on February 21 It was as crowded with students as I had ever seen it including legendary future meteorologists like Al Moller and John McGinley. The excitement level was high as were the volumes of voices due to both excitement and frustration because we were certain this was a major, or even unprecedented, event. The frustration was because it was impossible for us—or any organization that needed to track the weather in real-time on a national or regional basis (e.g., airlines like TWA, Braniff or Southern3 that served the affected areas)—to fully understand the extent and intensity of the storm. We students were shouting, “four flake snow at Gage (Oklahoma),” which was a reference to the diamond-shape arrangement of asterisks plotted from a report of heavy snow, or “hook reported from Jackson.” Roads were closed for days throughout the region. In Wichita, mail service was suspended on Monday, February 22, and even beyond in some parts of the city. It is still considered to be the city’s worst blizzard. My recollection is that the intensity of the blizzard was not adequately forecast. That seems to be confirmed by the fact the Sunday Wichita Eagle on the 21st did not include a news story forecasting a major snowstorm. FOOTNOTES Fultondale EF-3 Tornado of January 25, 2021 Central Alabama was involved within a warm sector ahead of an approaching cold front during the night of January 25th, 2021, featuring dew points in the low to mid 60s and surface-based instability reaching as high as 1,200 J/kg. Strong wind shear was in place which, combined with instability, favored a risk for severe storms. Upper-level troughing was displaced well toward the northwest, which helped to limit the number of severe storms, with just one or two occurring throughout the event. Apply to the Meteorological Satellite Applications Award Grant by March 25, 2021 Apply for the grant, and view more information at nwafoundation.org. The Call for Abstracts is open! Please review the information on guidelines, categories, important dates and this year's theme before submitting. Students and Active Military members can submit abstracts at no cost, and the fee for all other members is $40. The NWA Annual Meeting will be a hybrid event held on August 21 - 26, virtually, and in Tulsa, Oklahoma. We hope to see you there! #NWAS21

The full NWA Event Calendar is located in Member Connect. Have an event to include on our NWA calendar? Submit them to [email protected]! Seal Holders: Jennifer Perez and Jason Frazer Get to know our recent Seal Holders!

Jennifer Perez is the weekday morning meteorologist at WLUC TV 6 in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. While Jennifer has always been intrigued by weather, it was not until she was a senior in high school that she considered it as a possible career. At that point, she was encouraged to take a station tour at her local news station and after that, it all started coming together for her. ***

Jason Frazer is currently the weekend morning meteorologist at WKYC in Cleveland, a position he began in September 2019. However, meteorology is actually his third career. Schedule:

Thursday, February 25th

Tuesday, March 9th

Each Distant Social begins at 8:30 p.m. ET. More information about joining here. Are you hiring? Reach a variety of candidates through the NWA Jobs Corner. Current Jobs: Department Chair - Applied Sciences College of Arts & Sciences, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University-Worldwide (2/8/2021)

National Weather Association | 3100 Monitor Ave, Suite 123 | Norman OK 73072 | 405.701.5167 Publisher: Janice Bunting, NWA CEO Submit newsletter items to [email protected] |